Why use Polymorphism in OOP?

March 20, 2022

When I first came across the concept of Polymorphism in Object-Oriented Programming (OOP), it wasn’t obvious to me why it was important.

Let’s start with a hot take by Robert C. Martin:

…the thing that truly differentiates OO programs from non-OO programs is polymorphism.

It’s a bit of a blanket statement (Martin states that this was purposefully reductive), but I do agree that polymorphism is a central aspect of OOP. Let’s dig deeper!

What is polymorphism?

Since polymorphism has different meanings depending on context1, let’s align on what I meant by “Polymorphism in OOP”. In the earlier blog post, Martin explains it as different objects being able to accept the same message, implementing their own behaviour. I’ll paraphase his example:

some_object.do_something()We don’t actually know what some_object is! Nor does it actually matter. Many different implementations could replace some_object, and so long as they have the same interface (i.e. have the method #do_something), the program would still run.

Why use polymorphism?

In another blog post, Martin says:

There really is only one benefit to Polymorphism; but it’s a big one. It is the inversion of source code and run time dependencies.

It wasn’t initially obvious to me what that meant, so let’s concretise this with an example: caching in a web framework like Rails. There are multiple options out there for caches - for example, Rails supports a FileStore, a MemCacheStore and a RedisCacheStore. For the sake of illustration, imagine that the caches all had their own interfaces:

def example_method

# do stuff

if Rails.cache.is_a? NaiveFileStore

data = Rails.cache.search_for(key)

elsif Rails.cache.is_a? NaiveRedisCacheStore

data = Rails.cache.get(key)

end

# do more stuff

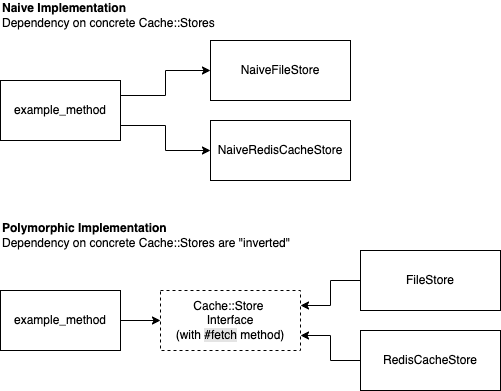

endAbove, our example_method has a direct dependency on NaiveFileStore and NaiveRedisCacheStore. If their interfaces change, or new kinds of store need to be supported, it will require changes in example_method.

Earlier, Martin talked about an inversion of dependencies (the “D” in SOLID) - practically, this means example_method and the different cache stores agree on an interface, and both depend on it. This makes all cache stores polymorphic! In Rails, all cache stores implement a #fetch method, so the above code becomes:

def example_method

# do stuff

data = Rails.cache.fetch(key)

# do more stuff

endThe code in example_method is more concise now, but that’s a side benefit; what’s important is it’s shielded from knowing which cache store is used, and how the store works. It just knows that some cache store exists (Rails.cache), and the cache store has agreed to implement a #fetch method.

We can visualise this “inversion” below - the arrows can be thought of as “dependency directions”:

Martin describes this as a “plugin architecture”:

This inversion allows the called module to act like a plugin. Indeed, this is how all plugins work… Plugin architectures are very robust because stable high value business rules can be kept from depending upon volatile low value modules such as user interfaces and databases.

With the new setup, the polymorphic cache stores can be swapped for each other without changing the code in example_method. New kinds of cache stores can also be supported by creating classes that implement #fetch and other methods as specified by ActiveSupport::Cache::Store.

In short, polymorphism makes it easier to extend or change aspects of our programs, without a rippling of changes throughout the entire program. (How do we determine the “aspects” to split our programs by? A good read would be Parnas’ classic 1972 paper.)

Afterword

While our cache example does rely on inheritance to make the polymorphic group explicit, inheritance is not a prerequisite. For example, each cache could be a completely unrelated class, and it still would work in Ruby as long as they had a #fetch method (this is also called “duck-typing”).

You may have spotted that Martin talks about inversion of “source code” in addition to runtime dependencies. I understand this has greater implications in compiled programs, but am not familiar enough to expound on it. Do leave a comment if you have an example!

There are many other neat examples relating to polymorphism. Here’s some I thought of:

- Martin Fowler’s refactoring book has a “Replace Conditional with Polymorphism” refactoring, which I think was neatly illustrated in this Sandi Metz talk.

- Many Behavioural Design Patterns rely on polymorphism, for example the Strategy, Command, Visitor etc.

- The NullObject is a neat way to support a null value or no-ops when your code relies on a Polymorphic interface. (Note that while Rails has a NullCache, it doesn’t solve the same issue that the pattern is meant to.)

- Ruby-specific example of a “Plugin Architecture”: Rubocop allows you to add your own custom cops without changing the library’s source code, because all cops are polymorphic!

- The definition I used for polymorphism is actually somewhat narrow, but seemed like a relatively common understanding in the context of OOP. The Wikipedia article on polymorphism shows a lot more breadth in the topic, and I think what is described above is known as single, dynamic dispatch. There’s some really good discussion on this in the Reddit thread for this post.↩

Psst - if this was useful, consider sponsoring a coffee (or sushi) for me 🙇♂️: