A 1972 paper and the Single Responsibility Principle

February 28, 2022

”A class should only have one reason to change” is a mantra that Object-Oriented advocates have chanted for years. Dubbed the “Single Responsibility Principle” (SRP), it remains somewhat abstract till this day ✨. Abstract enough, in fact, that it’s originator (Robert Martin) felt it worthwhile to explain again in a blog post - 14 years after he first wrote about it!

That blog post begins by referencing and quoting a 1972 paper, ”On the Criteria To Be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules” by David Parnas:

“We have tried to demonstrate by these examples that it is almost always incorrect to begin the decomposition of a system into modules on the basis of a flowchart.

We propose instead that one begins with a list of difficult design decisions or design decisions which are likely to change. Each module is then designed to hide such a decision from the others.”

The paper seemed significant, as Martin wrote that the SRP appeared “to align with Parnas’ formulation”. Could it demystify the SRP? What exactly was this paper about?

(Note: I’ve tried not to abstract too much of the paper, in the hope that you’d be able to draw your own conclusions as well.)

The System: KWAC Index

First, Parnas sets the stage - he would compare two criteria for modularizing a system, showing that one provided superior flexibility. The system in question was a KWAC (KeyWord Alongside Context) index generator.

KWAC was an indexing system for technical manuals, allowing a reader to quickly find where in the manual a keyword was used. In addition to showing the keyword, KWAC would show the rest of the sentence as well, it’s “context”:

To build the KWAC index, the system would take in file of sentences. Say the input file looks like this:

# cat input.txt

Program Development # line 1

On The Criteria # line 2For each line, the system looked through every word (the “keyword”), generating a KWAC entry. This was done by “circularly shifting” words that came before the keyword, appending them to the end. Then, it would sort the entries alphabetically. For example, given the above file, we’d get:

Criteria. On The [2] # "On The Criteria" is the original, "Criteria" was selected as the keyword here

Development. Program [1]

On The Criteria [2]

Program Development [1]

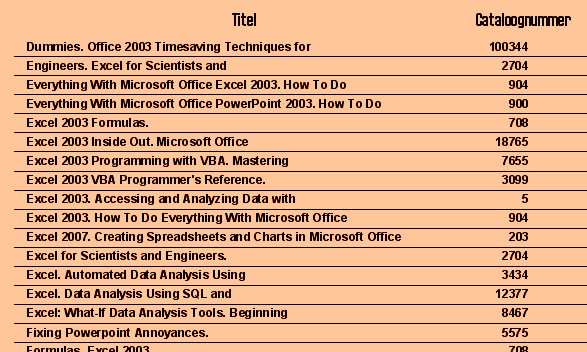

The Criteria. On [2]The next sections explain Parnas’ modularizations. This video explanation (starting from 17:16) helped me visualise and understand them, and I’m borrowing liberally from it 🙇♂️.

Modularization 1: “Flowchart”

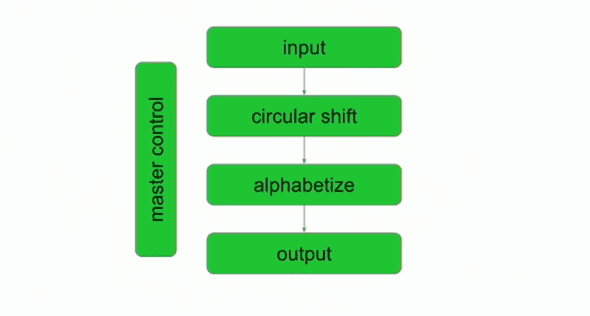

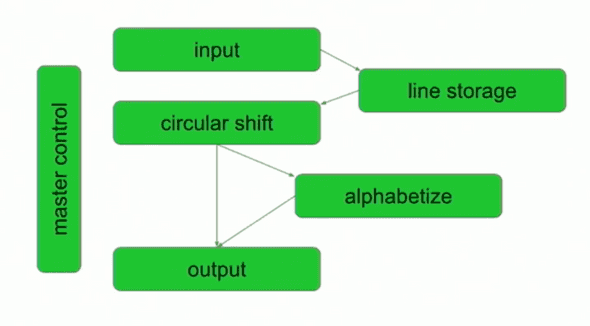

In the first modularization, Parnas modelled the problem as a flowchart, using the individual steps to break apart the modules (an approach which I’m guilty of applying at face value):

There’s a design flaw that isn’t obvious in the diagram - some common data that all modules need is stored in memory (a modern parallel might be a datastore), each module needing to know the low-level layout of the data. We’ll contrast this with Modularization 2 later.

Here’s what each module did:

- Input

- Parsed the input text file and stores in memory. We’ll call this “Characters”.

- The video (23:36) that explains this as (1.) memory at the time was accessed in groups of 4 characters (bytes), (2.) the input was split across these groups, with spaces in between words and lines.

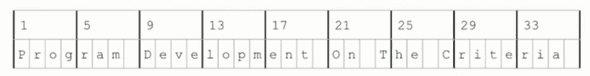

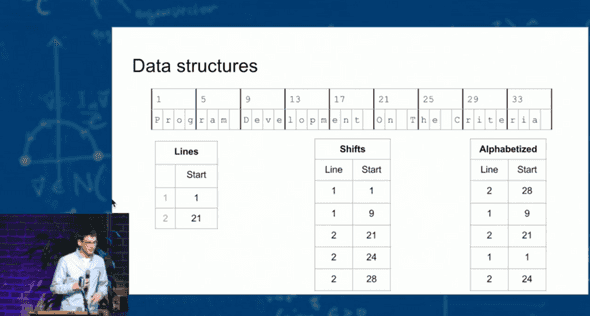

- The “Characters” could be visualised as follows:

- Note that in the above, line breaks are not distinguished from spaces. The module outputs a separate “Lines” structure for this, which is an array of “starting positions” for each line (e.g. above, Character 1 is the start of line 1, Character 21 is the start of line 2)

- Circular Shifter

- Accessing “Characters” in memory and “Lines”, it outputs an array of “Shifts”.

- Each “Shift” stored the line number, as well as the starting index of each word.

- Alphabetizer

- Accessing “Characters” and “Shifts”, it sorts the “Shifts” alphabetically and outputs them as “Alphabetized”.

- Output

- Accessing “Characters” and “Alphabetized” shifts, outputs the KWAC index (see “The System: KWAC Index”).

A helpful visual summary of all the outputs and stored data from the video explanation:

Modularization 2: “Information Hiding”

In this modularization, Parnas uses the criteria of “Information Hiding”. The definition is worth mentioning for it’s relevance to the SRP:

Every module in the second decomposition is characterized by its knowledge of a design decision which it hides from all others. Its interface or definition was chosen to reveal as little as possible about its inner workings.

Interestingly, what one might typically think as the general “responsibility” remains the same - modules are still mostly split along the same functionality lines. Instead, the major differences that I noticed in this modularization were:

Interestingly, what one might typically think as the general “responsibility” remains the same - modules are still mostly split along the same functionality lines. Instead, the major differences that I noticed in this modularization were:

- The details of how the characters were stored were encapsulated (hidden) via a new module, “Line Storage”. This meant that other modules did not have to know the low-level layout of the data. Instead, they would have a simpler interface to store and retrieve characters.

- The dependencies of modules were also tweaked, such that only two modules interact directly with “Line Storage”, as opposed to every module having to access “Characters” in Modularization 1.

- Modules in Modularization 1 depended on outputs from previous modules or common in-memory data. In contrast, modules in Modularization 2 depended directly on the interface of other modules (similar to calling methods on the module, a more Object-Oriented style).

Each module in greater detail:

- Input

- Like Modularization 1, also parses the input file, but this time initializes a “Line Storage” and inserts the data.

- Line Storage

- Think of it like an Object that has methods for inserting and retrieving characters by line (e.g. get Character 5 of Line 1, Word 2).

- Note: Unlike Modularization 1, this means callers do not need to know the nitty-gritty details of how data is stored.

- Circular Shifter

- Generates the circular shifts from Line Storage in an initialization step.

- Instead of outputting “Shifts”, the module itself provides an interface (like an Object) similar to Line Storage, but allows retrieval of characters by their shifts instead of lines (e.g. get Character 5 of Shift 1, Word 2).

- Alphabetizer

- Retrieving the characters from Circular Shifter, this modules sorts by alphabet and remembers the shifts in an initialization step.

- Instead of outputting the “Alphabetized” shifts, the module also provides an interface for getting ordered Circular Shifts indexes (e.g. tell me the shift number that’s in the 2nd sorted position).

- Output

- Uses Alphabetizer and Circular Shifter to generate the KWAC Index.

Comparison: Changeability

While other comparisons were made, the analysis of changeability speaks most to the SRP. Parnas begins by suggesting some “likely” change scenarios. Most require many modules to be updated in Modularization 1, but have a much smaller blast radius in Modularization 2.

Let’s take Scenario B below as an example - since all the modules in Modularization 1 depended upon a specific layout of “Characters” in memory, changing that layout would require changing every module. However, in Modularization 2, this would only require a change in the implementation of “Line Storage” - the interface could stay the same, meaning other modules were shielded from this change!

| Scenario | Modularization 1 | Modularization 2 |

|---|---|---|

| A. Deciding to store “Characters” in a different medium (e.g. filesystem) instead of memory | All modules | Line Storage |

| B. Deciding on a different way to store the “Characters” (e.g. group by words instead of every 4 characters) | All Modules | Line Storage |

| C. Deciding to store the full sentences of each circular shift instead of their indexes | Circular Shifter, Alphabetizer, Output | Circular Shifter |

| D. Deciding to change “Alphabetized” generation to be lazy or distributed (possibly due to a large dataset?) | Difficult to achieve as computation must be completed before output | Achievable as Output doesn’t need all the shifts to be “alphabetized” |

So the takeaway here is that good “information hiding” (a.k.a the SRP) results in a system that adapts more easily to changes.

Conclusion

So where does the paper leave us in relation to the SRP? Personally, I left with a better understanding of why it was important - it should result in a system that is easier to evolve with changes in requirements.

However, even with the (helpful) example, we are left with an abstract criterion of “information-hiding” and starting with a “list of difficult design decisions” or “design decisions which are likely to change”. The SRP, it seems, remains more art than science.

Discuss on Hackernews, or continue the conversation on Twitter.

(I apologise for the mix of American and British english 😆.)

Further Reading:

- Diego Ontaro’s talk and his example code in Go.

- KWIC Indexes in Wikipedia - note that the original paper calls it a KWIC index, but as Diego Ontaro explains, it’s actually a KWAC index.

- Parnas’ Original Papers: 1972 (which references an earlier paper written in 1971 with more implementation details).

- Adrian Colyer’s elegant and higher-level summary of the same paper.

- The paper does make a few other comparisons and points, I’ve left them out to keep this more focused to the SRP. A summary of what’s missing can be found in this gist.

Psst - if this was useful, consider sponsoring a coffee (or sushi) for me 🙇♂️: